What does freedom look like today? 7 Black American artists interpret the meaning of emancipation

| Published: 03-29-2024 12:25 PM |

Through July 14 at the Williams College Museum of Art you can view new works by seven of today’s leading Black American artists in “Emancipation: The Unfinished Project of Liberation.” The show, “conceived as a commemoration of the 160th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation … visualizes what freedom looks like for Black Americans today and the legacy of the Civil War today and beyond,” according to the museum’s website.

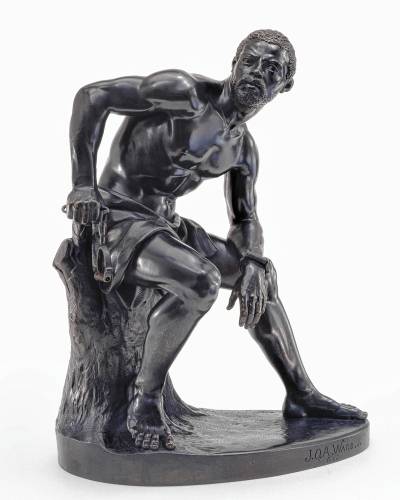

A bronze statuette, created in 1863 by the abolitionist sculptor John Quincy Adams Ward, inspires the show. Ward may be best known for the larger-than-life statue of George Washington fronting New York’s Federal Hall. “The Freedman,” which Ward sculpted before the end of the Civil War, depicts a man “on the cusp of liberation, having ruptured his bonds, though they are still present as a reminder of his enslavement.” It’s considered the first depiction of such an image.

“[The statuette] serves to be a larger conversation about what Emancipation means,” Maurita Poole said during a press reception. “That’s within the context of the United States and the various lenses.”

Poole is the executive director of Tulane’s Newcomb Art Museum and co-curated the exhibit with Maggie Adler of the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth, Texas. When the exhibit arrived, Destinee Filmore, an assistant curator at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, organized and added to the show with artifacts from the college’s Chapin Library.

“Ward had said about this sculpture that he intended it to be hopeful and inspirational,” Adler said during the reception. “He recognized that the work of emancipation wasn’t done, and that it would never be, in his lifetime.”

On a wall nearby is a sonar image of “Clotilda,” the last known slave ship to arrive in the United States, which illegally transported some 110 African men, women and children to Alabama in 1860, five decades after importing slaves was outlawed in the country. Remains of the vessel were discovered in the Mobile River in 2019. When the Civil War ended in 1865, a group of formerly enslaved people established Africatown on the north side of Mobile, Alabama.

As a link to the formerly enslaved people and Africatown, Letitia Huckaby, a multimedia artist who works in both textiles and photography, has created several large-scale works of African-Americans silhouetted in colorful, flowery cloth.

Poole noted that the silhouettes are reminiscent of black and white keepsake cameos, popular in the 19th century.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Carol Doucette of Royalston receives $15,000 from Publishers Clearing House

Carol Doucette of Royalston receives $15,000 from Publishers Clearing House

Magic comes to Red Apple in Phillipston

Magic comes to Red Apple in Phillipston

Plan calls for upgrades to Silver Lake in Athol

Plan calls for upgrades to Silver Lake in Athol

Royalston’s FinCom debates proposed salary increases

Royalston’s FinCom debates proposed salary increases

Locking up carbon for good: Easthampton inventor’s CO2 removal system turns biomass into biochar

Locking up carbon for good: Easthampton inventor’s CO2 removal system turns biomass into biochar

Liberty Taphouse to open in Athol

Liberty Taphouse to open in Athol

Adjacent is a work by artist Sadie Barnette, whose father Rodney was a founder of the Compton, California, chapter of the Black Panther Party and was subjected to FBI surveillance and harassment. Curious as to the contents of the federal dossier on her dad, in 2011 she requested the documents under the Freedom of Information Act.

The documents arrived five years later. Poring through the 500 pages, she found wildfires of allegations against her father.

Barnette has created larger-than-life graphite blow-ups of the FBI documents and highlighted sections, including the redactions, in pink, and adorned the pages with flowers and even a few faces of Hello Kitty.

“I make space for hope in my work,” Barnette said. “Not that I always feel hopeful but so that the work can be light when I don’t.”

A brightly ornamented octagonal table nearby is outfitted with glistening CCTV cameras.

Every few minutes, multidisciplinary artist Jeffrey Meris’ sculpture cycles, as the back of a white plaster torso scrapes against a grate, scattering plaster dust below. The torso is a cast of the artist’s body. When this dramatic and haunting process occurred, those in the gallery stood quiet.

In exhibit notes, Meris describes his installation: “In a work such as ‘The Block is Hot,’ I suspend a forty-pound cinder block from the wall using aircraft cable and a custom-welded mount to balance a Hydrocal cast of my torso.”

The grinding of the cast, “symbolizes societal pressures that grind down those seeking upward mobility.”

Meris then uses the plaster dust that falls from the torso as a medium to create patterns on large format adhesive roofing material, which hang next to the sculpture.

Adler said there was a “redemptive power to this disintegration. … This dust creates these universes through transcendence.”

“I think of the casts as surrogates for racialized violence,” Meris said in a 2022 interview with BOMB Magazine. “We look at Black bodies not as singular human bodies, but as these collective hieroglyphs.”

The use of the cinder block also has significance. Meris, who grew up in the Caribbean, said “homes made of cinder blocks [were] seen as more precious and more valuable because they can withstand weather, but it’s also this thing of ‘keeping up with the Joneses.’”

As an historical adjunct to the exhibit, Filmore found several antique accouterments relating to the African diaspora at the college library.

To consider transcendence, to go beyond ordinary limitations, she noted a 19th-century engraving of Ellen Craft in a display case nearby. Although enslaved, she could pass as white and her husband William believed that if he acted as her servant, they could flee to the north. She feigned illness to avoid conversations and to hide her illiteracy she faked having a broken arm. The couple made it to Boston and later sailed to England where they raised a family and authored the book “Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom.” In 1865 they returned to the South and established a school. A film of their odyssey titled “Everlasting Yea!” is in development with Amazon Studios.

Filmore also found an original copy of the Emancipation Proclamation and a pamphlet of an 1852 speech by Frederick Douglass as well as small, ceramic, late 1700s abolitionist medallions.

Also on view are two preliminary plaster head models that Augustus Saint-Gaudens created prior to designing Boston’s Robert Gould Shaw Memorial. Filmore’s research found that there were 82 upper Housatonic enlistees for the all-Black regiment and that two of Frederick Douglass’ sons joined the unit.

What may appear at first to be an over-sized toy jack is the creation of interdisciplinary artist Sable Elyse Smith. It is a commentary on the grave inequities and “ineffectual nature” of the American prison system, wherein Black people are incarcerated at six times the rate of white people; the steel structure is made of six uncomfortable stools found in jail visitor’s rooms, symbolizing the six prisons where Smith has visited her father, who is incarcerated, over the last 20 years.

Near the exhibit’s entrance, sculptor Hugh Hayden has reinterpreted Ward’s “Freedman” using 21st-century technology to do a 3-D scan and replicate identically the 1863 statuette.

“It’s the most gorgeous piece of 3-D printed plastic I’ve seen in my life,” Adler said.

The figure has the same pose, yet he is seated on an Adirondack chair and wears flips flops.

“It’s [Hayden’s] notion of the American Dream,” Adler said. “Comfort and middle class prosperity.”

Another striking sculpture is artist Alfred Conteh’s “Float,” a female form who has broken free from shackles and floats in a symbolic field of energy.

A site-specific work by artist Maya Freelon adds kaleidoscopic color to the exhibit. According to exhibit notes, “For Freelon, using recycled materials, or ‘maximizing the minimal,’ is itself an emancipatory act — dissolving barriers between ‘high’ and ‘low’ art and allowing accessible materials like tissue paper to take up space within historically inaccessible institutions.” Freelon’s work is heavily influenced by her grandmother, as well as her godmother and namesake, Dr. Maya Angelou.”

Almost 20 years ago she discovered “a beautiful accident” when a leaking pipe stained reams of the colorful paper. “Finding the watermarked paper changed the trajectory of my artistic career,” she wrote in an artist’s statement. She has since patented several processes in the complex dyeing of tissue and has created permanent installations throughout the world.

Conteh may have spoken for many when asked to describe freedom. “I see emancipation as a leveling of the playing field,” he said. The “destruction of whiteness as a construct when it comes to power and access to resources.”

“Emancipation: The Unfinished Project of Liberation” continues at Williams College through July 14. The museum is open Tuesday through Sunday from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Admission is free.