Ware author gives talk on ‘The Lost Towns of the Swift River Valley’ at State House

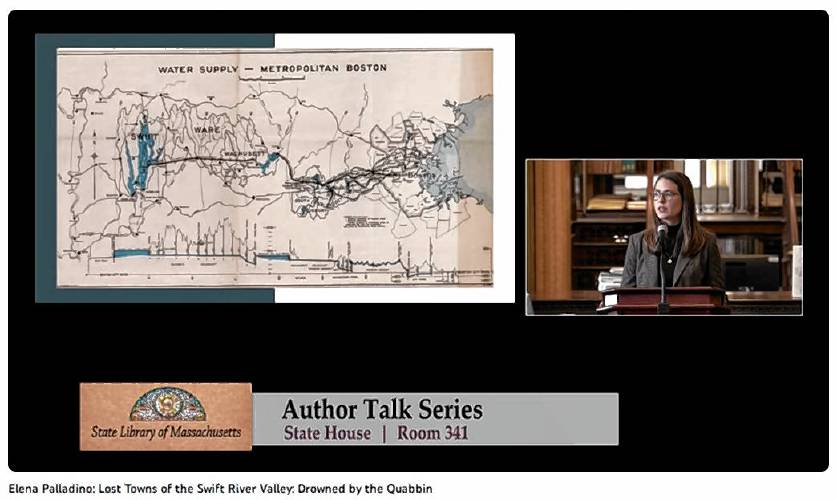

With hopes of providing context for proposed legislation, Ware author Elena Palladino was the featured speaker at the State Library Author Talks Series on Wednesday. SCREENSHOT

| Published: 12-07-2023 3:57 PM |

BOSTON — With hopes of providing important context for proposed legislation, a Ware author and historian was the featured speaker at the State Library Author Talks Series on Wednesday to discuss her book about three of the people who were forced to leave their homes for the Quabbin Reservoir’s creation.

Elena Palladino spoke for nearly an hour at the State House about how she came to write “The Lost Towns of the Swift River Valley: Drowned By the Quabbin” after moving from Framingham to Ware, into what neighbors called “the Quabbin House,” in 2015. Some recreational research opened a treasure trove of information about Dana, Enfield, Greenwich and Prescott — the four towns that were disincorporated 85 years ago to create the reservoir, thus ensuring Boston had improved water access. She became enthralled by the stories she learned and decided there was enough history to write her first book, which was published last year.

“It’s a beauty born of loss,” Palladino said of the Quabbin Reservoir.

The Great Boston Fire of 1872 — which destroyed 776 buildings across 65 acres in two days, killing at least 13 people and causing $60 million of personal property loss — generated conversation about how the state capital was in dire need of better access to water. The Quabbin region was ideal because it averaged 44 inches of rainfall annually and had hundreds of small streams flowing into the valley. At least 1,100 structures, including 650 homes, were dismantled. Property was taken by eminent domain if homeowners refused to sell their houses to the state for fair-market value. Anyone with a business in one of the towns received no compensation for it. An act of the state Legislature disincorporated the four “lost towns” on April 28, 1938.

Construction of the reservoir began in 1936, with filling commencing on Aug. 14, 1939. It was completed in 1946, when water first flowed over the spillway. The reservoir now consists of 412 billion gallons of water and covers 39 square miles, with 181 miles of shoreline, according to the state’s website.

Passage of a bill filed by state Sen. Jo Comerford, D-Northampton, and state Rep. Aaron Saunders, D-Belchertown, would provide for payments to Quabbin watershed communities for infrastructure such as conduits, pipes and hydrants, and to nonprofits providing health, welfare, safety and transit services in the region. It would also require more Quabbin representation on the board of the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority by adding two Connecticut River Valley seats and expanding the board so that three of the 13 board members are western Massachusetts residents.

The law would establish a 5-cent fee for every 1,000 gallons drawn from the Quabbin to be placed in a new Quabbin Host Community Development Trust Fund. This, Saunders said previously, would cost Boston ratepayers an average of six cents per month and generate an estimated $3.5 million annually for distribution to municipalities and nonprofits in the Quabbin watershed.

Palladino’s book focuses a great deal on the lives of former Enfield resident Marion Andrews Smith, as well as her friends, Dr. Willard Segur and Edwin Howe, a postmaster and manager of a general store. They were among the 2,500 people displaced so the Swift River Valley could be flooded. Palladino learned her Ware home had been owned by Smith and was called “the Quabbin House” because the wealthy descendant of a manufacturing company had pieces of her Enfield home removed and incorporated into the residence she had built in Ware. The pieces included floors, doors and the grand staircase. The construction company hired for the work, H.P. Cummings, still exists.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

At Wednesday’s talk, Palladino explained that she learned Smith’s father and uncle started the successful Swift River Manufacturing Co., which her brothers eventually took over. Palladino said Smith’s family was very active in the local community and she and her mother co-founded The Quabbin Club, a local women’s group that took on community welfare issues like education, civic engagement and public health.

Smith had no husband or children, but in 1930 her married chauffeur and housekeeper gave birth to a daughter they named after their employer. That child lived in the home for the first years of her life. Palladino tracked down this woman and hosted her in the home to learn some stories first-hand. The guest of honor even met Palladino’s daughter, who is also named after Smith.

“So my Marion is the third Marion to live in our house,” Palladino said.

She said Marion Andrews Smith never sold her house to the state, which eventually took it by eminent domain. However, she later settled with the state for a sum.

Palladino explained Segur was “a true country doctor” who traveled to patients by horse and carriage before owning one of the area’s first automobiles. The doctor was reportedly beloved in town, had a warm bedside manner, and accepted livestock and produce as payment. He also served as chair of the Selectboard and organized the farewell ball held at Enfield Town Hall on April 27, 1938, when some residents danced the night away before the four towns were disincorporated at midnight. Palladino said Segur led the grand march at the beginning of the emotional night and held a moment of silence at midnight “for the moment that the towns passed into history.” The doctor then led the band in a rendition of “Auld Lang Syne.” He died in January 1939.

Howe, Palladino explained, ran a general store as well as a telephone exchange out of his home. He was also the postmaster for several years and was likely the sixth generation of Howes to live in Enfield. He and Segur were good friends and lived within a short distance of each other.

Palladino said she was fascinated to learn something else the three had in common — out of resentment for having to abandon their homes, they refused to be buried at Quabbin Park Cemetery in Ware. Thirty-four cemeteries, consisting of 7,613 graves, were removed to create the reservoir and the state offered to inter the deceased and the displaced residents of the four disincorporated towns for free. Instead, however, Smith bought an expensive cemetery plot in Springfield and had all her family members laid to rest there.

“I thought this was really intriguing,” Palladino said.

She said some residents resisted the reservoir but others agreed Boston needed it. Many felt their sacrifices would not be forgotten, but Palladino feels they often are.

Reach Domenic Poli at: dpoli@recorder.com or

413-930-4120.

Sportsman’s Corner: The quest for the Super Slam

Sportsman’s Corner: The quest for the Super Slam Annual ‘Food-A-Thon’ returns

Annual ‘Food-A-Thon’ returns Erving Town Meeting voters back Care Drive housing project

Erving Town Meeting voters back Care Drive housing project North Quabbin Notes, May 9

North Quabbin Notes, May 9