Slavery North: Researcher brings initiative, $2.65M grant to UMass to explore, tell story of enslaved people in northern U.S. and Canada

| Published: 03-11-2024 5:00 PM |

AMHERST — In film, literature, paintings and other forms of art, palm trees and warm climates are almost always the settings depicted for slavery in North America, from the plantations of the American South to the transatlantic ships transporting human cargo between tropical locations.

As a Canadian of immigrant Jamaican parents, University of Massachusetts art historian Charmaine A. Nelson has recognized that New England and other parts of the northern continental United States, as well as her home country, have largely ignored their involvement in slavery — not only in the history books, but in the arts.

“What is not written about is the colder places, like the U.S. North, and its integral part in slavery,” Nelson said.

Nelson, who came to UMass in 2022, has spent her academic career trying to bring this history to light, largely through in-depth research, even as it is shut out from what children learn in schools.

“Canadian slavery is not taught anywhere in the curriculum,” Nelson said.

An art historian, provost professor of art history and founding director of Slavery North, which she created in 2020 and brought to Amherst, Nelson recently earned a $2.65 million Mellon Foundation award, the largest such grant ever made to UMass Amherst.

What this will mean is potentially growing a field that Nelson said remains in its infancy, with the Slavery North Initiative providing society a better understanding of a neglected history while uncovering the blind spots. University-based research into the transatlantic slave trade is not unusual, she said, but almost all are related to how slavery developed in and around the tropics.

“Slavery North is a global first to focus on Canada and the U.S. North,” Nelson said. “We’re alone in that.”

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

Work on Pinedale Avenue Bridge connecting Athol and Orange to resume

Work on Pinedale Avenue Bridge connecting Athol and Orange to resume

PHOTOS: Enchanted Orchard Renaissance Faire at Red Apple Farm

PHOTOS: Enchanted Orchard Renaissance Faire at Red Apple Farm

Rice’s Roots Farm owner plans for community involvement for land’s future

Rice’s Roots Farm owner plans for community involvement for land’s future

Orange Selectboard declares armory as surplus property

Orange Selectboard declares armory as surplus property

‘Arrive Alive’ shows Athol High School students the dangers of impaired driving

‘Arrive Alive’ shows Athol High School students the dangers of impaired driving

Nature lovers gather at Adams Farm for hawk watch

Nature lovers gather at Adams Farm for hawk watch

The Mellon grant sets Slavery North — currently an initiative that aims to become an institute — on the path to being a research center. Nelson said the hope is to promote racial inclusion, belonging and understanding and allyship, while showing how the history of slavery manifests itself in continuing anti-Black racism with roots that date back to the 1400s, even as certain countries and regions have been allowed to forget.

“All of these dimensions of anti-Black racism today, the Black maternal health crisis for example, or that we get stopped more if we’re driving a nice car, or we get asked for an ID when paying for luxury goods, goes back to the hyper-surveillance and the brutalization of our ancestors in the period of slavery,” Nelson said.

The initiative will eventually be located in the building that for 60 years housed the Newman Catholic Center, until it was sold to the university and the church moved to a new building nearby. Inside, there will be offices, exhibits and rooms for research presentations and lectures.

The heart of the initiative is the fellows program, which allows for growth of the field of research into slavery outside conventional locations. “Since there are not many scholars studying slavery in the U.S. North and Canada, the ability to grow the field is limited,” Nelson said.

The fellows program will include four undergraduate honors students, slots being offered exclusively to UMass Amherst students and students at the Five Colleges; two artists in residence each year; and one fellow in each of the several categories that include master’s of arts, doctorate and visiting research fellows. With students in the program pursuing their master’s theses and doctoral dissertations, there will be a pool of people actively providing synergy and a supportive and collaborative environment. There also will be a three-person staff.

Plans for the Slavery North initiative include a lecture series, Black History Month panels, an academic conference and an academic book, a podcast series, workshops, art and cultural exhibitions, and a historical database housing primary sources of enslaved residents in Canada and the U.S. North, as well as building connections with partners such as Historic Deerfield.

Nelson was first drawn to examining slavery in Canada when studying at Concordia University in Montreal, observing the representation of Black women in 20th-century painting. Following the completion of her doctoral work, she spent 17 years at McGill University in Montreal, after initially starting in 2001 at the University of Western Ontario.

Then, at the Nova Scotia College of Art & Design in Halifax, Canada, she founded the Study of Canadian Slavery and served as the Tier 1 Canada research chair for Transatlantic Black Diasporic Art and Community Engagement. After publicly expressing concerns about being undermined as a Black academic, she accepted an offer to come to UMass, contingent on her being able to bring the re-envisioned Slavery North project with her.

“This was an easy decision because both of these regions have historically sought to erase their participation in transatlantic slavery,” Nelson said, having familiarity with UMass after hosting a guest seminar for UMass graduate-level students called “Contemporary Scholars, New Art History: Writing the Histories of Transatlantic Black Diasporic Art in 2020.”

Art history, she said, has been one of the last disciplines to grapple with the impacts of colonialism, imperialism and slavery on both art and cultural production, representation and consumption. Nelson said one can’t do justice to art history without this understanding, but she had to do a lot of the research on her own.

“European empires did not merely create archives of documents, they created a 400-year archive of art and visual culture, much of which was strategically used to justify slavery and reify Eurocentric ideals of race. Therefore, Western art has largely been about the representation of human beings within racial hierarchies,” Nelson said.

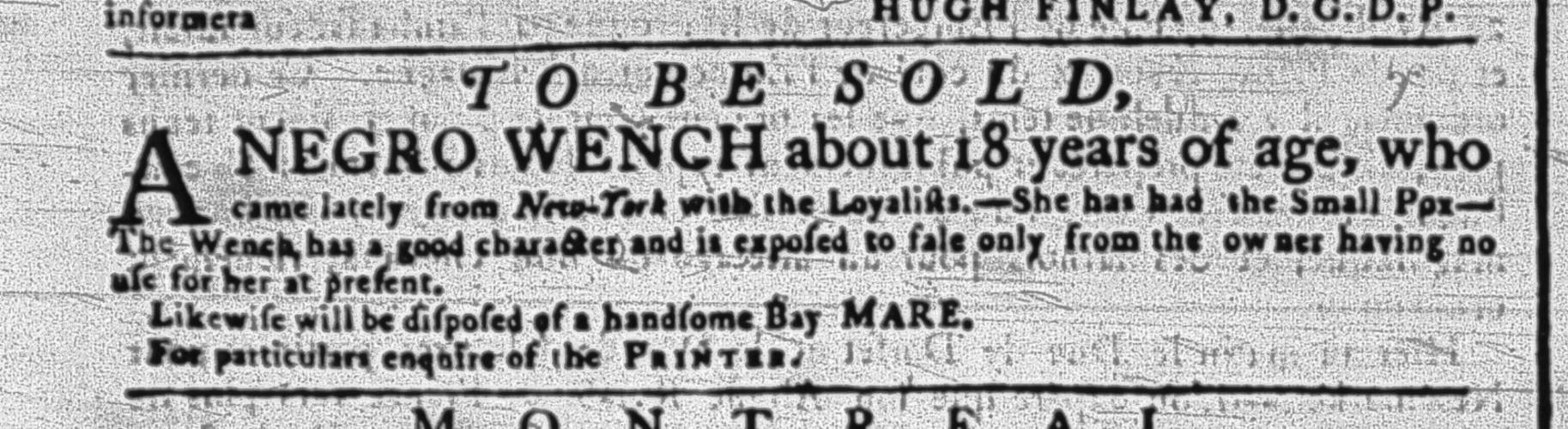

Yet because slaves were considered property, there are often meticulous records. In the tropics, for instance, there are plantation ledgers and bills of sale for enslaved persons, along with logs from the West Indian merchants that list rum, sugar, molasses, coffee and slaves.

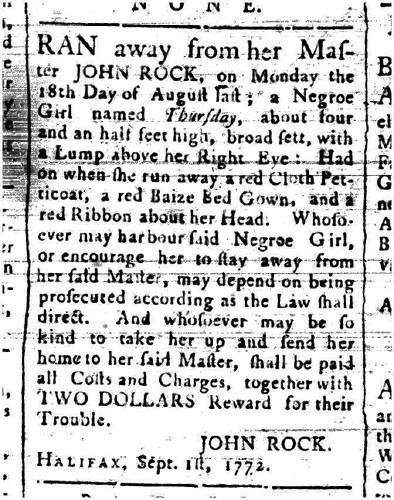

In the North, slave auction advertisements in Colonial-era newspapers and ads for fugitive or runaway slaves, often with detailed descriptions of the person’s appearance, even down the clothing being worn, are among the primary sources connecting this information to this region. “They are profoundly useful, but horrific,” Nelson said.

The hope is to get much of what is learned into databases that researchers can use, with much easier access to these records.

“There’s no dearth in material,” Nelson said. “The problem is how it’s being catalogued.”

Having art historians be part of this is critical, she said, as what is eventually produced by filmmakers, playwrights, painters and performance artists is more likely to get out to the public at large.

“That, to me, is a huge component of this work,” Nelson said.

Scott Merzbach can be reached at smerzbach@gazettenet.com.

Franklin County reps speak to House budget amendments

Franklin County reps speak to House budget amendments Employee pay, real estate top Erving Town Meeting warrant

Employee pay, real estate top Erving Town Meeting warrant