Latest News

Sportsman’s Corner: Turkey time

Sportsman’s Corner: Turkey time

New fed rules may force Mass. action on PFAS

New fed rules may force Mass. action on PFAS

PHOTO: Learning leather

PHOTO: Learning leather

North Quabbin Notes, April 11

North Quabbin Notes, April 11

Director of Village School in Royalston steps down

ROYALSTON – Village School Director Rise Richardson, who has been there since the doors opened in 1989, has announced she has stepped down from the position.Richardson has been the school’s director since 1994, and said she had decided that it was...

Athol Salvation Army Corps joins Boston Marathon volunteers

ATHOL — Though they may not have been among the runners, the Salvation Army Athol Corps played an important role in the 128th Boston Marathon.The corps sent two vehicles — their mobile feeding unit, also known as a “canteen,” and a minivan — to help...

Sports

High Schools: Two-run first inning propels Pioneer baseball past Turners

Turners Falls pitcher Joey Mosca did all he could to hold down a potent Pioneer lineup on Tuesday. Mosca gave up two runs in the first inning but settled in from there, not allowing a run the rest of the way while striking out six. The Turners bats...

Softball: Hannah Gilbert allows two hits as Franklin Tech knocks off Blackstone Valley, 7-3 (PHOTOS)

Softball: Hannah Gilbert allows two hits as Franklin Tech knocks off Blackstone Valley, 7-3 (PHOTOS)

UMass basketball: Matt Cross reportedly enters transfer portal

UMass basketball: Matt Cross reportedly enters transfer portal

Baseball: Sam Connors, Mahar get past Smith Academy for win No. 2 (PHOTOS)

Baseball: Sam Connors, Mahar get past Smith Academy for win No. 2 (PHOTOS)

Opinion

Walt Gorman: Fed up

The solar eclipse did not change my life, but I very much enjoyed it. I doubt I’ll be around for the 2044 eclipse, but if I am, I just might travel to North Dakota to see it.According to the US ambassador to France and other US officials, former...

Maggie Baumer: Access to prosthetics and orthotics for physical activity a right, not a privilege

Maggie Baumer: Access to prosthetics and orthotics for physical activity a right, not a privilege

Pat Hynes: Nuclear weapons bills need action

Pat Hynes: Nuclear weapons bills need action

Nikki Garrett: A joy to join in on Earth Day cleanup

Nikki Garrett: A joy to join in on Earth Day cleanup

Police Logs

Athol Police Logs: March 12 to March 19

ATHOL POLICE LOGSTuesday, March 126:45 p.m. - Male party into the lobby regarding a shop vac he lent to someone and they are refusing to give it back. Party was advised of his options. Attempted to contact involved party, negative contact, a voicemail...

Athol Police Logs: Feb 19 to Feb. 27

Athol Police Logs: Feb 19 to Feb. 27

Athol Police Log Feb. 4-18

Athol Police Log Feb. 4-18

Orange Police Log 12/1-13

Orange Police Log 12/1-13

Athol Police Log 11/8-26

Athol Police Log 11/8-26

Arts & Life

Crunch time for matzo: An easy-to-make sweet treat that’s Passover Seder-friendly

Passover begins this coming Monday night. This eight-day holiday means many things to many people: the survival of the Jewish people in the book of Exodus, the overall history of Judaism, and even the last supper of Jesus.This year Easter came more...

Obituaries

Robert E. Thayer

Robert E. Thayer

Robert E. "Bob" Thayer Athol, MA - ATHOL - Robert E. "Bob" Thayer, 90 of Athol passed away Sunday, April 14, 2023, in the Athol Hospital. He was born on July 13, 1933, the son of Robert H. ... remainder of obit for Robert E. Thayer

Chris N. Boyle

Chris N. Boyle

8/5/1956 - 4/11/2024 ORANGE, MA - Chris Boyle, beloved father and husband, passed away on April 11, 2024 at home. Chris led a life of unwavering dedication to his family, a steadfast co... remainder of obit for Chris N. Boyle

Donn K. Clifford

Donn K. Clifford

PHILLIPSTON, MA - Donn K. Clifford, 74, of Barre Road, died on Wednesday, April 10, 2024 at Heywood Hospital in Gardner. Born in Gardner on August 15, 1949, he was the son of Robert Cliffo... remainder of obit for Donn K. Clifford

Shirley Anne Bailey

Shirley Anne Bailey

PEPPERELL, MA - Shirley Anne Bailey, age 89, passed away quietly on Sunday, March 31, 2024, at Ayer Valley Nursing and Rehabilitation. She was a long-time resident of Pepperell, MA, and was... remainder of obit for Shirley Anne Bailey

Franklin County youth tapped to advise governor’s team

Franklin County youth tapped to advise governor’s team

Athol Police Logs: March 27 to April 10, 2024

Athol Police Logs: March 27 to April 10, 2024

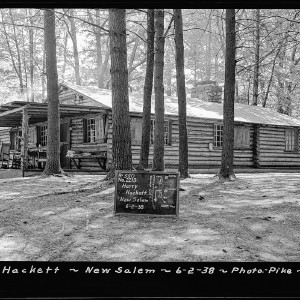

A Page from North Quabbin History: Quabbin Reservoir photo archives

A Page from North Quabbin History: Quabbin Reservoir photo archives

Historical society presents history of Nichewaug

Historical society presents history of Nichewaug

Equity, income concerns flagged in free college debate

Equity, income concerns flagged in free college debate

School nurse resigns after Orange administrators discover lack of license

School nurse resigns after Orange administrators discover lack of license UMass trustees OK 2.5% tuition increase

UMass trustees OK 2.5% tuition increase Athol Town Manager says next fiscal year may be the ‘most challenging’ in the last decade

Athol Town Manager says next fiscal year may be the ‘most challenging’ in the last decade Heywood Healthcare cites progress made since bankruptcy filing

Heywood Healthcare cites progress made since bankruptcy filing High schools: Mahar softball can’t stay with Northampton in 20-6 loss (PHOTOS)

High schools: Mahar softball can’t stay with Northampton in 20-6 loss (PHOTOS) My Turn: The pecking order revolution: Massachusetts’ fight for animal rights

My Turn: The pecking order revolution: Massachusetts’ fight for animal rights Spotlight on women in classical music: Brick Church Music Series’s season comes to a close, April 28-29, with Champlain Trio

Spotlight on women in classical music: Brick Church Music Series’s season comes to a close, April 28-29, with Champlain Trio Ready for their close-up: Pothole Pictures announces a season of curated film screenings, live music and $1 popcorn

Ready for their close-up: Pothole Pictures announces a season of curated film screenings, live music and $1 popcorn You’re up next: Western Mass open mic scene heats up post-pandemic

You’re up next: Western Mass open mic scene heats up post-pandemic Sounds Local: Fun for the whole family: Meltdown, a book and music fest for kids, returns to Greenfield this Saturday

Sounds Local: Fun for the whole family: Meltdown, a book and music fest for kids, returns to Greenfield this Saturday