Latest News

Sportsman’s Corner: Quabbin opens this Saturday

Sportsman’s Corner: Quabbin opens this Saturday

North Quabbin Notes, April 18

North Quabbin Notes, April 18

New fed rules may force Mass. action on PFAS

New fed rules may force Mass. action on PFAS

Quabbin region studied for MWRA expansion

As House Democrats eye the expansion of its public drinking water service area, the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority (MWRA) is considering whether the communities where that water comes from should finally get to reap the benefits of the...

Phillipston board opens talks on new police chief

PHILLIPSTON – Police Chief Kevin Dodge recently announced his intention to retire from a post he has held for more than a decade, and the Selectboard is reviewing the options for hiring his successor.The chief’s current salary is just under $85,000...

Most Read

Orange man gets 12 to 14 years for child rape

Orange man gets 12 to 14 years for child rape

Carol Doucette of Royalston receives $15,000 from Publishers Clearing House

Carol Doucette of Royalston receives $15,000 from Publishers Clearing House

Wheeler Mansion in Orange to reopen as bed and breakfast

Wheeler Mansion in Orange to reopen as bed and breakfast

Phillipston board opens talks on new police chief

Phillipston board opens talks on new police chief

Royalston Selectboard mulls options for full-time police

Royalston Selectboard mulls options for full-time police

Editors Picks

Sportsman’s Corner: Turkey time

Sportsman’s Corner: Turkey time

Equity, income concerns flagged in free college debate

Equity, income concerns flagged in free college debate

Athol Town Manager says next fiscal year may be the ‘most challenging’ in the last decade

Athol Town Manager says next fiscal year may be the ‘most challenging’ in the last decade

Historical society presents history of Nichewaug

Historical society presents history of Nichewaug

Sports

High schools: Abigail Schreiber’s hit propels Frontier softball past Greenfield, 3-2

It wasn’t looking good for the Frontier softball team heading into the bottom of the sixth inning against Greenfield on Thursday. The two-time defending state champs held a 2-0 lead, but the Redhawks were able to get a run back in the sixth. Seventh...

Baseball: Frontier handles Greenfield 12-2 in five-inning victory (PHOTOS)

Baseball: Frontier handles Greenfield 12-2 in five-inning victory (PHOTOS)

The Real Score: Curveballs and casinos rarely save cities

The Real Score: Curveballs and casinos rarely save cities

High schools: Frontier girls tennis picks up 5-0 win over Turners (PHOTOS)

High schools: Frontier girls tennis picks up 5-0 win over Turners (PHOTOS)

Florence’s Gabby Thomas gearing up for 2024 Paris Olympics

Florence’s Gabby Thomas gearing up for 2024 Paris Olympics

Opinion

Jessica Zhang: Weigh your choices — Solar power a better alternative

In his recent letter [“‘No’ means higher energy prices,” Recorder, March 26] Jim Bates is right that fossil fuels have powered societies across the globe — nobody disputes that. It’s the reality of pollution and carbon buildup in the atmosphere that...

My Turn: Saving planet Greenfield

My Turn: Saving planet Greenfield

Gary Seldon: Solar Roller Earth Day River Ride

Gary Seldon: Solar Roller Earth Day River Ride

Police Logs

Athol Police Logs: March 12 to March 19

ATHOL POLICE LOGSTuesday, March 126:45 p.m. - Male party into the lobby regarding a shop vac he lent to someone and they are refusing to give it back. Party was advised of his options. Attempted to contact involved party, negative contact, a voicemail...

Athol Police Logs: Feb 19 to Feb. 27

Athol Police Logs: Feb 19 to Feb. 27

Athol Police Log Feb. 4-18

Athol Police Log Feb. 4-18

Orange Police Log 12/1-13

Orange Police Log 12/1-13

Athol Police Log 11/8-26

Athol Police Log 11/8-26

Arts & Life

Hitting the ceramic circuit: Asparagus Valley Pottery Trail turns 20 years old, April 27-28

A lot can change in 20 years: Presidents and other politicians come and go, new cultural fads and technologies emerge, clothing styles morph, and music and movies take on different dimensions.In these parts, one tradition hasn’t changed. Since 2005,...

Obituaries

Nancy C. Skowrowski

Nancy C. Skowrowski

Nancy C Skowronski Royalston, MA - Nancy C Skowronski, born in Worcester, MA on January 1, 1943, lived a captivating life, filled with vibrant memories and impactful experiences that created... remainder of obit for Nancy C. Skowrowski

Robert E. Thayer

Robert E. Thayer

Robert E. "Bob" Thayer Athol, MA - ATHOL - Robert E. "Bob" Thayer, 90 of Athol passed away Sunday, April 14, 2023, in the Athol Hospital. He was born on July 13, 1933, the son of Robert H. ... remainder of obit for Robert E. Thayer

Chris N. Boyle

Chris N. Boyle

8/5/1956 - 4/11/2024 ORANGE, MA - Chris Boyle, beloved father and husband, passed away on April 11, 2024 at home. Chris led a life of unwavering dedication to his family, a steadfast co... remainder of obit for Chris N. Boyle

Donn K. Clifford

Donn K. Clifford

PHILLIPSTON, MA - Donn K. Clifford, 74, of Barre Road, died on Wednesday, April 10, 2024 at Heywood Hospital in Gardner. Born in Gardner on August 15, 1949, he was the son of Robert Cliffo... remainder of obit for Donn K. Clifford

With eye toward teaching firearm safety, Mahar’s Junior ROTC adding air rifles

With eye toward teaching firearm safety, Mahar’s Junior ROTC adding air rifles

Partnership succeeds in protecting Lake Monomonac forestland

Partnership succeeds in protecting Lake Monomonac forestland

Franklin County youth tapped to advise governor’s team

Franklin County youth tapped to advise governor’s team

Athol Police Logs: March 27 to April 10, 2024

Athol Police Logs: March 27 to April 10, 2024

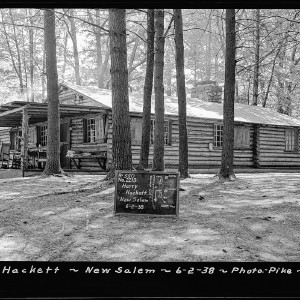

A Page from North Quabbin History: Quabbin Reservoir photo archives

A Page from North Quabbin History: Quabbin Reservoir photo archives

Mitch Speight and Joan Marie Jackson: City should follow constitutional ruling on property takings

Mitch Speight and Joan Marie Jackson: City should follow constitutional ruling on property takings Columnist Johanna Neumann: Reaping the rewards of rooftop solar

Columnist Johanna Neumann: Reaping the rewards of rooftop solar Best Bites: A familiar feast: The Passover Seder traditions and tastes my family holds dear

Best Bites: A familiar feast: The Passover Seder traditions and tastes my family holds dear Valley Bounty: Your soil will thank you: As garden season gets underway, Whately farm provides ‘black gold’ to many

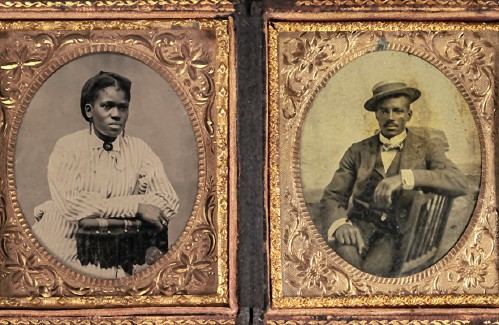

Valley Bounty: Your soil will thank you: As garden season gets underway, Whately farm provides ‘black gold’ to many Painting a more complete picture: ‘Unnamed Figures’ highlights Black presence and absence in early American history

Painting a more complete picture: ‘Unnamed Figures’ highlights Black presence and absence in early American history Earth Matters: From Big Sits to Birdathons: Birding competitions far and near

Earth Matters: From Big Sits to Birdathons: Birding competitions far and near